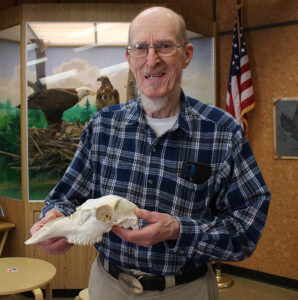

He’s ‘Mr. Montezuma’

For Chuck Gibson, a wildlife refuge has refreshed his life

By John Addyman

Pick a Friday morning, anytime from April to November.

Arrive around 8 a.m. — and watch carefully.

You’ll be refreshed by the clean air, a big sky and the sounds and sights of wildlife all around you.

The one thing that doesn’t fit the picture is the lone car, slowly driving and occasionally stopping at the end of a scene that lies out as far as you can see.

Far away you can see the New York State Thruway, vehicles gliding by soundlessly because they’re so far away.

Closer to you are areas of cattails, open water, grasslands and brush.

And birds. Waves of birds. Ducks. Geese. Owls. Herons. Gulls, bald eagles. Coots and harriers and osprey and Plovers and Mergansers and wigeons and teals and swallows and blackbirds.

Your perspective from here, the Visitors’ Center at the Montezuma Wildlife Refuge, is of a vast, relatively flat area that touches Wayne, Seneca and Cayuga counties.

Scanning the horizon, you see that single car turning toward you from far away and you wonder, “What’s that guy up to?”

A meteorologist does his homework to predict the weather for you.

Reporters do their homework to tell you what’s new.

Chuck Gibson, 85, is about to tell you exactly where you can find the birds you came all this way to see.

He’s in that car. He’s known as “Mr. Montezuma.”

“On my day of work, I come in about 8 a.m.,” Gibson explained. “I do a tour of the property, see what’s going on, what birds are available at that time, check three or four locations throughout the complex and then at 10 a.m. we open the visitors’ center and I have some knowledge of what’s available to pass on to the visitors as far as what wildlife is out there. Most basically, it’s ducks and geese.”

For a birder who has come to Montezuma, Gibson — and the other volunteer service center representatives who work there — is an invaluable resource. He is the guy who knows, who can go through your want-to-see list and tell you where to spot the refuge’s abundant wildlife.

He has a little more to offer because he started his work life a long time ago on the Erie Canal, which borders part of Montezuma. He knows the history of the canal because he’s lived through part of it, when major commercial traffic glided through the locks and waterway.

Those canal days were “interesting times,” Gibson said. “I drove a small boat with a kerosene tank on top of it, a gravity feed, and I went around and filled the kerosene lanterns on the bridges and cleaned the lenses if they got smokey. I trimmed the wicks so the lamps stayed clean.”

In those days, commercial traffic on the canal was 24 hours a day. He graduated from that job to lockmaster.

“I worked out of Lock 27 in Lyons,” he said, “covering three locks, one in Lyons and two in Newark. You never knew what was going to happen: I’d get a call from my compatriot in Newark that there’s a boat coming and I had to go meet that boat and follow it through, then I would call ahead to the next lock and let them know they had traffic headed their way. This was commercial traffic, of course.”

He went on to a career as the head custodian at Lyons Central High School. With job experience on the canal and in Lyons, he hit retirement age and pulled the plug on work.

“I said ‘good-bye. I’m not going to do this job anymore,’” he said.

That was August 2000.

“The first day of school the next month, I went down to the local coffee shop and watched everybody go by on their way to work and said, ‘Thank God I don’t have to do this anymore,’” he added.

Gibson and his wife came to Montezuma in 2005 to enjoy some of the activities there.

“We got acquainted with the place and programs. We went out one night to celebrate our anniversary,” he said. “About 2 a.m., she woke up screaming, ‘There’s something terribly wrong!’ She had a brain aneurysm, which was like turning the lights off: all of a sudden, I was a widower.

“After her funeral I said to myself, ‘What the hell am I going to do now?’ So, I went over to Montezuma, talked to Andrea VanBeusichem, the visitor services manager, about donating one day a week and it progressed from there. That was 2008.”

One of his first projects was trapping and putting transmitters on two short-eared owls, one a mature bird, the other a juvenile.

“Almost immediately, one of the birds, the adult bird, got predated by maybe a red-tailed hawk or an eagle. We found the transmitter and a few scraps of that bird. The juvenile bird had wanderlust. We’ve been tracking that bird halfway down Cayuga Lake,” he said.

The younger bird came back to Montezuma and made a hummock in a cattail swamp — a place that’s somewhat snow-free — where he spent the winter. “We knew he was healthy and we left him alone after that,” Gibson said.

As Gibson settled in on Fridays at Montezuma, he was pressed for a higher level of service. He became a member of the Friends of the Montezuma Wetlands Complex, joined the board and eventually served as president for seven years. He has now been a familiar face at the visitors’ center and the Audubon Center on the other side of the refuge for 17 years.

Montezuma is growing

The Montezuma National Wildlife Refuge was born in 1937 when the federal Bureau of Biological Survey bought the land. The Civilian Conservation Corps began work there the next year. Today Montezuma has 18,000 acres of protected land, roughly a 3.5-mile square park. 10,000 of those acres are federal land, 8,000 belongs to the state. The state Department of Conservation has a working office on the site.

And the acreage isn’t static. Montezuma is growing slowly.

Gibson explained: “Whenever land becomes available, we try to purchase it. We have to pay market price, of course, but we have a unique situation where Ducks Unlimited and a couple of other organizations that have deep pockets can buy the land today and they’ll hold it for us until the federal or state government acts to set money aside to pay them back and take control. Then they’ll use that money to purchase other properties. It’s a symbiotic relationship, you might say.”

The Civilian Conservation Corps built the road that circles around the property in 1937 and also replaced farmland on Howland Island with a building site that was eventually used in World War II to house German prisoners of war.

Gibson’s knowledge of the canal spills into what he learned at Montezuma.

“When the Erie Canal was dug, originally it was four feet deep and 40 feet wide. Then it was deepened to seven feet and when they put the barge canal in, the Erie Canal was 12 feet deep and they rearranged the path,” he explained.

“What we’re sitting on now,” he said, speaking from the Montezuma Visitors’ Center, “this is all spills from the building of the canal. Our Wildlife Drive borders the canal for at least two miles, then it borders the Thruway, which was cut through the refuge back in the 1950s.

It’s the birds

How did Chuck Gibson get hooked by Montezuma?

It’s the birds.

“When I was a Boy Scout going through summer camp, I got interested in birds that showed up in the woods and it kind of snowballed from there. I’ve probably been birding for 60 years, anyway,” he said. “Birds are fascinating to watch and to track and understand where they fit in the ecosystem. And Montezuma is a great place to see birds. That’s what this place is all about — a resting place on the migration path. Twice a year we have an influx of ducks and geese and other birds who are going from the south to the north, then back from the north to the south.”

“Chuck is very much at home at the refuge,” said VanBeusichem, the visitor services manager. “But not only the refuge but the Audubon Center and state conservation area — the wetlands complex. He knows the land, the people, he’s knowledgeable about the work we do, he volunteers; he does whatever we need.

“He’s been a great spokesperson, too, out in the community. Talking to people about his time at Montezuma is a big part of his life. His passion and his knowledge about Montezuma come through.”

From the dead of winter, Gibson is looking forward to spring and some of the changes being planned in the refuge and those who will come to view them.

“You meet a lot of very interesting people from all over the world,” he said. “You never know who’s going to walk through that door or where they’re from. They are all on their best behavior. They’re all interested in the wildlife, what we’re doing here and how we do it, what’s available.

“We don’t know what’s going to show up this coming year. We know the eagles are going to be here on the Seneca Trail, which is closed while they’re nesting.

“And this year, there will be more aggressive mowing along the shoulders of the wildlife drives to open up some of the viewing that’s been obscured by cattails, to give people a better view of the wildlife without needing to get out of their cars and disturbing wildlife. I think that’s a good move.”

The visitors’ center is a federal building, due to be enlarged to house some federal employees from Cortland. Gibson is concerned that may mean losing the Friends of Montezuma store and a lovely viewing room. But things aren’t certain and time will tell.

He’ll be there to keep an eye on things.

“I plan to live to 100,” he said. “It’s nice to have a plan.”