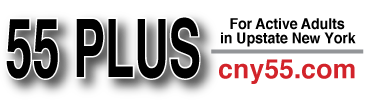

The Remarkable Beth Baldwin

Executive director for The Baldwin Fund says it’s her mission in life to help breast cancer victims, find a cure for the disease

By Tim Bennett

Beth Baldwin-Keuchler may not be an actor like her four brothers, Alec, Daniel, Billy and Stephen. But she plays a real-life role as passionately as any part they could ever play — as an untiring advocate for breast cancer victims and the executive director for The Baldwin Fund, a nonprofit organization that raises funds for breast cancer research.

Founded in 2001 by her mother, who was a breast cancer survivor and originally called the Carol M. Baldwin Breast Cancer Research Fund of CNY — the name was changed on Carol Baldwin’s request before she died because she saw it more as a family-supported charity.

In speaking with Baldwin in a study room at Onondaga Free Library in Syracuse, she talked about growing up in Long Island with four rambunctious brothers; how celebrity status affects her family outings today; the Baldwin Fund; and supporting women battling breast cancer.

Looking at the celebrity of her brothers you may think being a Baldwin means “made in the shade” with few challenges. But that would be far from the truth. Growing up in Massapequa, a suburb of Long Island, the oldest child of a high school history teacher-coach and a stay-at-home mom with six children, Baldwin has faced her share of heartaches and trials.

The first rude awakening of life’s unpredictability came when her parents took in three of their nieces for long periods of time during Beth’s childhood because of parental neglect due to alcoholism. Years later, Baldwin would adopt the baby of one of those cousins due to her cousin’s mental illness.

More shocks came when her father-in-law died of lung-throat cancer in 1981, her mother-in-law of breast cancer in 1982, her father of an aneurysm from lung cancer in 1983 and her own baby in 1984. “Now, that’s a lot of devastation due to death and disease. You’re not supposed to lose a baby and so many parental figures in your 20s,” she said during our interview.

You would think someone at 70 with so much tragedy and hardship behind her would be somber, morose and perhaps, a bit depressed.

But Baldwin defies that stereotype. During our interview, she was upbeat, friendly, direct and thoroughly engaged.

Here’s an excerpt of our conversation:

Q. Tell me about yourself. Where did you grow up, your childhood and education?

A. I was born in Massapequa, Long Island. My dad was an SU student from Brooklyn. My mom grew up in Syracuse and also went to SU where they met. They got married in 1954 after they both graduated and moved down to Long Island. My dad had a degree from Syracuse law school but he didn’t go into law. He took a job as a school teacher at Massapequa High School. It was a heartbreaking move for my mother because she grew up in Syracuse with a big family with five sisters and a brother. But she did and then she had six children. First was me, then my brother, Alec. Then Daniel, Billy, my sister, Jane, and my youngest brother, Stephen. We were all raised down there.

Q. Where did you go to school?

A. My dad taught at Massapequa High School so we weren’t allowed to go to the same high school. So, we went to Berner High School. But believe me, if we ever got in trouble at Berner my dad would hear about it. I went to college at C.W. Post, also on Long Island and majored in criminology, but I didn’t become a criminologist or work in the police department — I got married young at 19 and then got very busy with children — five girls and a boy.

Q. Living with four brothers who would later become actors, do you have any funny stories from your childhood?

A. It was crazy growing up in my house. My dad was a history teacher and also a coach for different sports so he was usually at the school until very late, which meant my mom was basically raising six kids. My brothers would get away with murder. When my dad got home and there had been trouble, he would ask me who was responsible and I would always say, “I didn’t do it. They did.” And he always believed me because it was true. I was too afraid of my dad. They, of course, would complain that I was always “ratting” them out, but I was the oldest and dad knew he could trust me. We lived in a neighborhood that had lawyers and doctors but we struggled to get by because male teachers did not get paid a lot in those days.

Here is a good story for you. There was a private golf club across the street from us, which we did not belong to. One day the boys took some clippers, like they were playing army men and made a hole in the chain-link fence, went in, tied back the piece they’d cut out, played golf and then went out the same way they came in. They had friends on the other side of the golf course doing the same thing. They kept their clubs and balls in the woods. They knew exactly when everyone left the club and also the timing of when the sprinkler would go on and off. They had maybe 45 minutes to play. Amazingly, they never got caught.

Q. Did you ever join them in their mischief?

A. Not playing golf. But Alec and I would sometimes have a lemonade stand just outside the fence in the parking lot and we’d also sell golf balls. We’d find a lot of them in our yard and we would polish them up with Windex and then put them in an egg carton. If someone said, “Hey, wait a minute! This looks like the ball I just hit!” we’d say, “Oh no, can’t be. You’d have to be a really bad golfer to hit it into our yard.” And, of course, no one wanted to be called a bad golfer, so they never pushed it.

Q. So what brought you to Syracuse and how did the charity start?

A. The main reason we came back was my dad died at 55 in 1983 of an aneurysm from lung cancer and, my mom always wanted to come back to Syracuse. My husband and I had bought our family home in Long Island and mom had lived with us for four years after Dad died so by then, she was ready. It’s no surprise my dad got lung cancer since he was a rifle coach at the school and the firing range was in a room which was not ventilated with asbestos in the walls. If you are in a sealed room like that for 32 years, that’s what happens. Studies have shown that an unusual amount of teachers get breast cancer and other cancers possibly related to working in those old school buildings.

So my husband and I, our six children and my mom, all moved up here in 1987. We bought a house on Onondaga Hill with an in-law apartment and my mom continued to live with us. I was a full-time mom. Then my mother got diagnosed with breast cancer in 1989. Right away she said, “I want to do something that’s going to change this.” Shortly after that, she researched with two other women who also had breast cancer, Micki Wilder and Nancy Dunigan, along with her plastic surgeon, Dr. Hadley Falk, a charity that they could bring to Syracuse. The goal was to help women talk to other women about what they were going through. Nobody was speaking about it. It was taboo at the time to use the word “breast” and “cancer.” So they opened a chapter of the Susan G. Komen Foundation in 1990, which was out of Texas. They founded it here and ran fundraisers to support it for many years. Then the people from Stony Brook University approached her to help fund a breast cancer clinic down there that they wanted to name after her, but she did not want to fund the new building, only the research taking place inside it. That opened in 1996. When Komen started expanding nationally, my mom decided to start another charity in Syracuse in 2001. This way she could make sure all the funds they raised went to local institutions. She also decided to focus on raising money for breast cancer research so as not to conflict with Komen, which concentrated on education and awareness of the disease.

Q. When did you start working for your mom’s charity and how did your role evolve through the years?

A. I was her caretaker, you know, even when she was younger and going through breast cancer. And then she wanted to do the Komen Foundation and my siblings were involved at that point, too. And they’d have the Race for the Cure, they’d have a gala or they’d have a motorcycle ride and my mother was involved in organizing it. She even got the Hotel Syracuse to give them a free office. My mother was always able to get people to donate, always. And then she kind of pulled me into it, where I’d be taking her everywhere and helping wherever I could. Eventually, as she got older, I was the one running the day-to-day operations of the charity.

Q. You spend many hours sitting with breast cancer victims as well as organizing fundraisers for breast cancer research. How do you support women who have breast cancer?

A. I may start out by picking them up for their appointment. I ask if they want coffee. I listen to their stories, like maybe their sons or husbands didn’t want to come with them to the appointment. Maybe they are divorced. I tell them the names of my children and a bit about my life. I always tell them this story. When I was 35, I got my first mammogram and I had a lump in the same breast at the exact location as my mother. My mind could have gone in the direction that I got it too, but I am the kind of person, like my dad, who said, “I don’t have it until they tell me I have it.” So, I talk that kind of talk into people. In other words, until they take out the tumor and bring it to the lab and know for sure, you don’t have it.

I might be sitting down with a woman and her husband and they are hysterical and shaking. I ask them if they want me to go in with them to see the doctor. If I do, I often explain what the doctor is saying because a lot of time they don’t understand it. I’ve listened to thousands of cases. I haven’t had breast cancer myself so I never say, “I know how you feel” because I don’t fully, because my results came back negative, but I’ve been to the ledge. And I’ve known family members who have died of breast cancer, my mother in-law and my two aunts and those who have survived it, my mom and many others.

Q. How do you manage to stay upbeat and positive when you are constantly with people who are battling cancer? Doesn’t it get a bit overwhelming?

A. You sound like my brother, Alec. No, I don’t let it because I have so much faith in what I’m doing. I’m very resistant to getting overwhelmed because I know it’s God’s will for me. I think that certain people have gifts to be able to withstand that heaviness. It’s like a doctor. How do you say to somebody, “Your mother’s dying” or “Your kid is going to die?” That doesn’t mean I don’t cry sometimes.

I have a horse story that helps me stay on track. You see, in Central Park, they have these horse-drawn buggies and the horses have these pads or what they call blinkers, on the sides of their eyes that keeps them from looking to the right or the left. I look at that as my faith. In other words, I’m not going to look to the right to fear or to the left to cancer. I’m just going to look straight ahead, which to me is God. I really believe this is my calling so I don’t see it as a burden.

Q. Over the many years of research on breast cancer, have there been any big discoveries?

A. Yes. There was a major one discovered in 2022 by one of the researchers that we support, Dr. Leszek Kotula, who is a professor and the assistant research director at Upstate Medical University. He has found the gene to metastatic breast cancer. So, he knows he’s got the gene. Now he needs to make the compound of the drug and go through all the trials — animals first and then humans. It will be an infused medication like a chemo but it won’t make you sick. I think he’s got a five- to six-year period to do this and he’s in two years already (article available at https://tinyurl.com/53mw9t6v)

Q. So, that’s going to help doctors to treat it once someone has it?

A. No. It will stop it. You treat it once you have it. So, if you have a metastasis, this gets injected into you, and it will stop the metastasis from growing. This is very exciting because our charity provided the seed money to get him going and then he got millions more from other organizations to get to this important stage.

Q. What are some projects you are working on now?

A. I’m very determined to help the Upstate Cancer Center achieve National Cancer Institute designation — which is the gold standard for cancer programs. This requires us to raise $50 million to recruit top cancer researchers from all around the world to come to Syracuse and do research on specific cancers. An arm of the institute, for example, would be for breast cancer. The other would be for the top cancers of New York state like lung, ovarian and prostate. I could keep going. There are seven or eight of them. Researchers are not going to move to the tundra of snow in Syracuse if they live in India. You have to bring them here and you have to pay them. I’m not saying millions of dollars, but you have to pay them correctly. So when that money comes in, it draws interest. The other $25 million will do what I do now, but at a higher level. So part of this is to get the doctors. The other part is to give them the funding that they need for their research. If you are going to find a cure for cancer it’s going to come from research.

Beth on How Alec Baldwin Got His Start in Acting

“My brother, Alec, was working in a restaurant as a waiter and a casting director for NBC came in and loved his voice and said, “Why don’t you try out for a daytime soap opera? There’s auditions in a couple of weeks.” So the woman gave him her business card. He had gone to George Washington three years but he decided he didn’t want to go into politics or become a lawyer so he transferred to the Lee Strasberg School at NYU to study acting and he’s only been there a couple of months before he meets this person in the restaurant.

He goes to the audition — he’s maybe 20 or 21 years old — and when he comes back home he tells us, “I got the job!” We all look at him like he’s crazy. We’re telling him, “You’re going to college and you’re getting on a soap opera during the day? You’re out of your mind?” He says, “Well, they’re going to call me on Friday.” This is like Tuesday or Wednesday. On Friday, nobody calls. So, of course, his brothers all start picking on him. Monday morning the phone rings and it is NBC and they tell him he needs to get an agent and a lawyer because he got the part.

My dad was so proud of him he’d bring a portable TV set to his seventh period current events class and the current event was watching Billy Aldridge on “The Doctors” because it was his son. I mean it was hysterical. But my dad didn’t think it would last. “Oh, he won’t be doing this very long,” he’d tell my mother.

So Alec did daytime TV and then he got on “Knots Landing”, a nighttime show, which meant he was progressing as an actor. And the first movie he ever did was “Beetlejuice”. And “Beetlejuice”, they thought, was not going to be a successful movie. And then it becomes like a cult classic and people watch it all the time. So basically all of my brothers were kind of looking at their oldest brother like, if this idiot can do it, why can’t we? So, I guess you could say that Alec broke the ice for the rest of them.”

Beth On How She Adjusted to Having Famous Brothers

“I must admit sometimes people ask me very odd questions like: ‘Do you talk to your brothers?’ I talk to them every day. Like, ‘Do they come visit you?’ ‘Do they buy you nice things?’ I mean, why would I even answer that? To me, I only look at them as my brothers. I forget sometimes they’re famous when people ask for their autograph or to take their picture. This could happen when we are having private time as a family at a café somewhere. We just want to visit and be able to talk about our families, how the kids are doing. I’m not asking about what movies they’re doing. My siblings also want to know about the charity because they are involved and it was started by our mother. Sometimes they look at me to see if it bothers me. You know, I’ve had times when they’ve gone to key events in my children’s lives, like my oldest daughter’s communion, and my brother, Alec, had to come in late just to avoid all the staring. Then, when it was all over we went over to the doughnut and coffee table and a politician walks up to me and asks, ‘Do you think we could get a picture?’ I go, ‘Look, this is about Jessica today. This is her day.’ Alec then turns to me and says, ‘Let’s go eat dinner.’ It ruins it for them.

Or you get somebody in a restaurant and I’ll be with my brother and somebody will walk up and they don’t have his same political views. They shake hands and then start to argue. If that happens, I look right at that person and I say, ‘I live here. My brother is visiting me right now.’ This is my attitude on my brother’s work: You go and pay $10, $15 to watch a movie. You paid the money. You watched the movie. You got the service. The person in the movie shouldn’t be obligated to let you take their picture at any time, sign their autograph for you whenever you want or get yelled at by you.”

The Baldwins in 55 PLUS

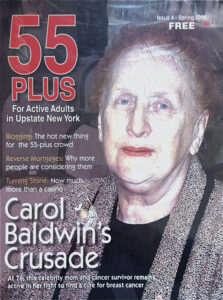

Beth Baldwin is the third member of the Baldwin family to be featured on the cover of 55 PLUS.

Beth Baldwin is the third member of the Baldwin family to be featured on the cover of 55 PLUS.

Her mother, Carol Baldwin, then 76-year-old, was on the cover in the spring of 2006 (Issue No. 4). She discussed her own fight against breast cancer, her efforts to help breast cancer patients and her work to raise money to find a cure for the disease. “I am a survival,” she told 55 PLUS at the time. “I’m going to keep going as long as I possibly can do find a cure.” Carol died in May 2022 at the age of 92.

Her mother, Carol Baldwin, then 76-year-old, was on the cover in the spring of 2006 (Issue No. 4). She discussed her own fight against breast cancer, her efforts to help breast cancer patients and her work to raise money to find a cure for the disease. “I am a survival,” she told 55 PLUS at the time. “I’m going to keep going as long as I possibly can do find a cure.” Carol died in May 2022 at the age of 92.

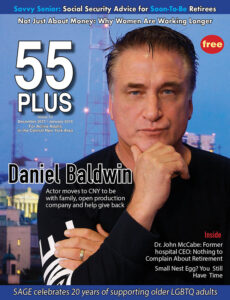

Beth’s brother, Daniel Baldwin, was on the cover of our December 2017 – January 2018. At the time, he had moved to the Oswego County village of Cleveland, on Oneida Lake, to stay closer to his mom, start a movie company and work to combat addiction. He left the area in 2019.

Beth’s brother, Daniel Baldwin, was on the cover of our December 2017 – January 2018. At the time, he had moved to the Oswego County village of Cleveland, on Oneida Lake, to stay closer to his mom, start a movie company and work to combat addiction. He left the area in 2019.